From the 2023 HVPA National Conference

Taylor Anderson BS (The University of Queensland – Ochsner Clinical School), Lily Morrison MPH, Marissa Scott BS, Audrey Shawley BA, Kathy Jo Carstarphen MD, MPH

Background:

At this pivotal moment in healthcare, medical students are uniquely situated to incorporate principles of high-value care into their future practice. The Students and Trainees Advocating for Research Stewardship (STARS) program is a year-long fellowship that provides medical students with tools to promote resource stewardship.1 The fellows at Ochsner Clinical School set out to develop and implement a Value Based Care (VBC) curriculum that includes didactic and interactive components to educate medical students about how to incorporate VBC in their future practice.

Objective:

To describe the curriculum and its evaluation so educators may build upon these resources and implement VBC curriculum for future physicians.

Methods:

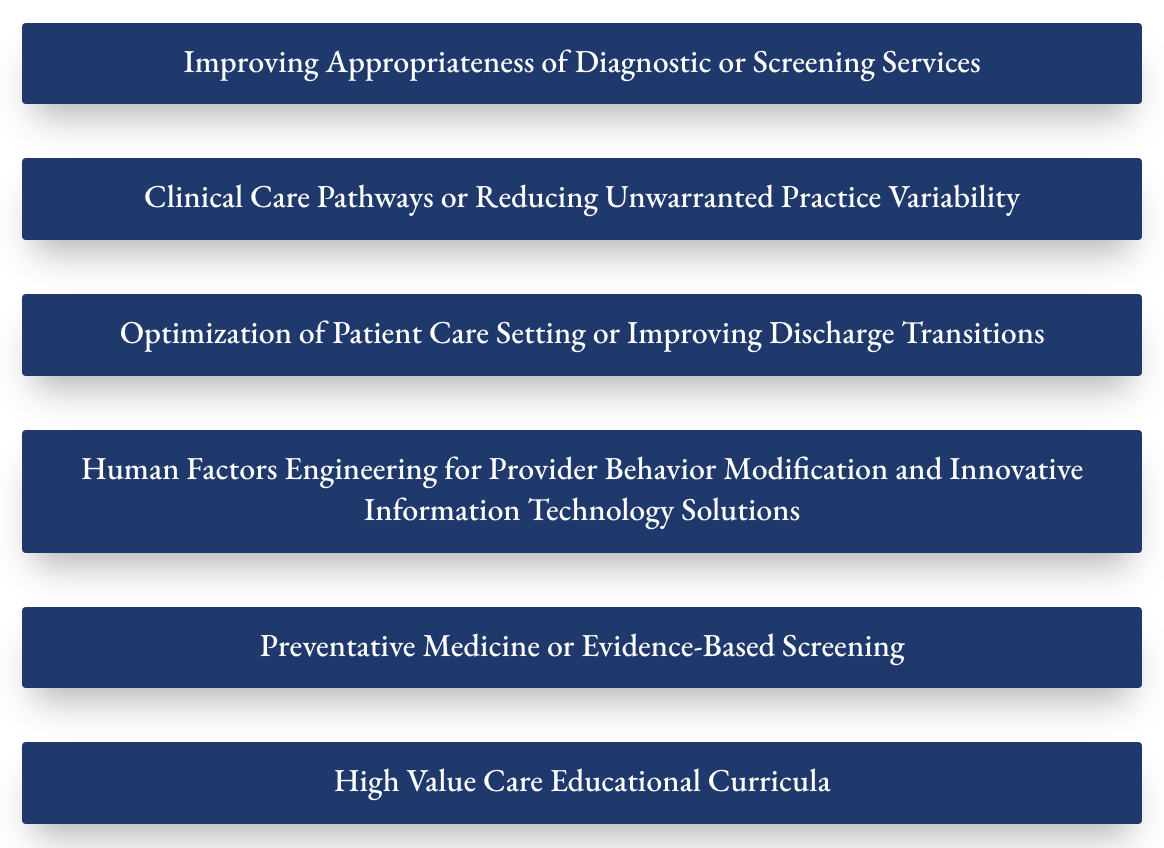

A curriculum was developed based on the STARS Fellowship training materials, Choosing Wisely Campaign recommendations, and Costs of Care organization resources.1-3 The curriculum consists of three interventions that introduce medical students to VBC concepts and the practical application of this knowledge.

First, students participated in hour-long didactic sessions that included an introduction to value-based care, a discussion on mitigating financial toxicity, an example patient journey, and two interactive quizzes. Qualitative data was collected before and after each session based on the know, want to know, and learned (K-W-L) framework.4 Thematic analysis was conducted and emergent themes were identified to explore gaps in student knowledge.

Second, small-group workshops were organized to teach third-year medical students a value-inclusive approach to the oral presentation. SOAP-V modifies the traditional SOAP format, creating a cognitive forcing function that promotes discussion of high-value, cost-conscious care.5 Pre and post surveys will be used to evaluate participant learning. Participant written reflections will be collected for qualitative thematic analysis.

Third, a case competition modeled after problem-based hackathons will allow students to apply their knowledge.6 Teams will be tasked with identifying value deficits and proposing creative solutions for a student-authored case. Finalist teams will present their findings in a grand-round style presentation. Pre and post surveys will be used to collect participant data relating to VBC learning and competition satisfaction. Quantitative analysis will be conducted with descriptive statistics to determine competition efficacy and opportunities for improvement.

Results:

Participants were asked: 1) what they already know about value-based care, 2) what they would like to know, and 3) what they learned. Responses were reviewed and coded independently by two researchers with a calculated intercoder reliability of 0.9. Emergent themes were organized into domains based on the K-W-L framework. Themes relating to “know” include: VBC misunderstanding and preventative care importance. The “want to know” domain included: VBC applications and implementation. Lastly, for “learned”: physician’s role in cost reduction, unnecessary service burden, and student opportunities for change.

This curriculum builds upon previous VBC research and addresses gaps in medical student education. It has been designed to be easily adapted to new educational environments, thereby reaching larger audiences. Ongoing data collection is being conducted for phases 2 and 3.

Conclusions:

Medical students lack education about healthcare waste, cost of medical care, and the accompanying financial toxicity patients face. Our initial results highlight gaps in student understanding and an interest in learning how to apply VBC concepts. We hope to further contextualize these learning opportunities as we continue to gather data. We believe that integration of this curriculum within medical schools is an effective way to train future physicians to deliver value-based care.